...............................

...............................

Typical electric squirrel cage motors

Believe it or not, nearly everyone you know has at least one induction generator and probably more. That's right! You say that is impossible... well, read on!

Within every home in America there are motors that can be operated as generators. They may not be labeled as generators, but they will function just the same. These motors are often called "squirrel cage motors" and are in washing machines, dryers, water pumps and other devices too numerous to mention.

...............................

...............................

Typical electric squirrel cage motors

Besides being numerous and cheap, they will generate AC voltage of the purest sinewave. They use no brushes and do not produce any RFI.(Radio Frequency Interference) A motor converted to an induction generator will power flouresent and incandesant lights, televisions, vcr's, stereo sets, electric drills, small power saws and other items.

OK, what is so great about it? There is nothing complicated about the conversion, no weird rewiring, no complicated math...nothing! There are no brushes to wear out.

They can not be overloaded; if too much of a load is applied to the generator, it simply quits generating. Removing the load will usually cause the generator to start again. Speeding up the motor will help if it doesn't start right away.

Yes, but... are there problems? Well, there is no active voltage regulation, but keeping it within a tested load rating can keep it within any voltage parameters that you set. I feel that a voltage range between 105 and 126 volts is perfectly reasonable.

A motor converted to an induction generator will not start another squirrel cage motor unless that motor is about 1/10 of the horsepower of the induction generator. In other words, a 1 horsepower motor used as an induction generator will start a 1/10 horsepower or less, squirrel cage motor. It is best to NOT use an induction generator to drive motors. The added inductance of the motor will cancel out the capacitive reactance of the capacitors and cause the generator to quit producing electricity.

The generator will not start under a load. Not a problem! You shouldn't attach any load to a generator until it is at running speed. This is actually kind of a fail-safe feature.

So far, that is about all of the problems that I've found and I consider those minor.

By adding capacitors in parallel with the motor power leads, and driving it a little above the nameplate RPM, (1725 RPM ones need to turn at approximately 1875 RPM, and 3450 RPM ones at 3700 RPM) the motor will generate AC voltage! The capacitance helps to induce currents into the rotor conductors and causes it to produce AC current. The power is taken off of the motor power leads, or the capacitor leads, since they are all in parallel.

This system depends upon residual magnetism in the rotor to start generating. Almost all the motors I've tried begin generating just fine on their own, with the appropriate capacitor connected of course! If it doesn't start generating, try speeding the motor up. That will usually get it going. However, it is extremely rare to find one that doesn't start.

If a motor doesn't start generating on the very first try, then apply 120 vac or even 12 or more volts DC to the motor for a few seconds. That will usually work to magnetize the rotor and your generator will start by itself from then on.

It is important to not shut the generator down with a load connected to it. This tends to demagnetize the rotor and can cause it to not self-energize. That is, the motor will turn, but it will not produce voltage. It is not a serious problem since the rotor can be remagnetized by following the instructions in the paragraph above.

I've only found one motor that would not consistantly generate (out of a dozen or so that I've tried over the years) and it was one with a bunch of wiring coming out of it; it may have been a multi-speed AC motor. I had a 120 volt AC relay in the circuit that temporarily added a 200 uf starting capacitor across the permanent 160 uf running capacitor (Using the Normally Closed contacts) to get it generating. When 120 volts was produced, the relay contacts opened up and removed the 200 uf from the circuit. That worked, but it was not dependable. I just gave up on that one.

The capacitors used must be the type designated as "running" capacitors and NOT "starting" capacitors. Starting capacitors are used for a very short time, usually less than a second or two, and would be destroyed by being connected across the AC line continously. Running capacitors are designed to be connected while the motor is powered.

NOTE: Make sure the caps say, "NO PCB's". PCB's aren't used anymore for capacitor construction because it was a dangerous chemical composition. If the caps are old, and you are not sure, don't use them. Be safe!

It is necessary to experiment to find the best value of capacitance to get one working. Start with about 150 to 200 uf for motors 1 horsepower and under. More capacitance equals more voltage output. The final value should be able to produce about 125 VAC when it is putting out 60 hertz with no load. Then plug in100 watt light bulbs until the voltage drops to what ever lower limit you set. Mine will do about 1050 watts before dropping to 105 VAC.

............................

............................

Typical Running Capacitors...GOOD! .......................Starting cap...Bad!

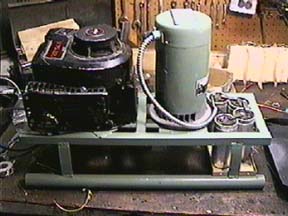

In the following example, I used a 1 horsepower motor from a Sears water pump that I bought at a junk yard for $10.00. This motor was capable of operating off of 115 or 230 volts at 13 or 7 amperes respectively.

Typical waterpump motor

Motor: A. O. Smith 1 Horsepower : 115 / 230 VAC : 13 / 7 AMPS : 3450 RPM

Capacitor: 200uf 330vac. This was made by paralleling 4 capacitors that were 65uf, 35uf, 50uf and 50uf. All of these were rated at 330vac or better. All test results are from this capacitor set. (NOTE: The final version of this generator has 225uf of capacitance.)

Output Capability: This Induction generator has an no load voltage of 125.9 VAC at 60 hz. The generator successfully powered 1050 watts of lightbulbs with a voltage drop of 10.9 VAC to a full load voltage of 105 vac. During the power test, the generator was driven by a 1.5 horsepower electric motor and there was a loss of RPM when the load was increased. I attribute some of the voltage drop to this lack of driving power.

The ex-motor, now an induction generator is driven by a well used 3.75 HP B&S lawnmower engine. A total of 950 watts of lights were ran for about 15 minutes with the generator only getting warm. The voltage went from 126 volts open to 110 volts AC under this load.

Notice the capacitor set-up. Here I am trying a suggestion found in an old article, which stated that it is possible to use DC electrolytics connected in series, + to +, and - to - in an AC circuit. I have 4 capacitors rated at 850 uf, 400 VDC in series, for a total of 225 uf @ 1600vdc . The connection is like this:

AC Lead to motor 0----+||------+||------||+------||+----0 AC Lead to motor

Will it work? They seem to be doing just fine, with no sign of heating at all. If they fail or deteriorate, I'll post the info here on the web page.

New!New! I used this generator for 12 hours continously in the NC8V field day in very hot temperatures and adverse conditions on the weekend of June 26, 1999. The capacitors did NOT FAIL OR CHANGE in the least. So I can recommend this use of DC capacitors as a viable option. Of course standard disclaimers apply!

...................

...................

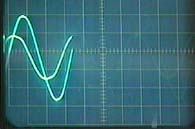

Top Trace: 60 hertz / Bottom Trace: Capacitor phase shift. Overlaid waveforms.

These traces show the phase shift within the capacitor/inductance combination. The inductance is from the motor windings. Traces were made by feeding a 10 v p-p 60 hertz voltage through a 47 ohm resistance to the capacitor/inductance combination. The top trace in the left picture is the input voltage to the resistor while the bottom trace is across the capacitor/inductance.

Waveform at 950 watt load.

Note the enlarged gasoline tank. I made this modification in mid June of 1999. This generator was used at the NC8V field day event and performed perfectly where it ran approximately 12 hours. This one gallon tank allows the generator to run for 4 and 1/2 hours without refueling.

Notes on gasoline engines:

Make sure you get a reliable gasoline engine. Nothing is more frustrating that to have to fight with the engine while you need electricity!

Nearly all the B&S engines that are used on lawn mowers with a direct connected mower blade depend upon this blade to act like a second flywheel for the engine. They have a primary aluminum flywheel inside the engine cover. The aluminum flywheel does not provide enough inertia to work without the blade. The symptoms are backfiring, jerking starter rope and difficulty in starting. You will probably have to change the aluminum flywheel to a cast iron one. The cast iron ones are pretty common in horizontal engines that are used in rototillers, etc. Usually junk yards or small engine shops will have them. (Also, make sure the magnet matches the one on the original flywheel; they have either one or two magnetic poles which are very obvious by sight.) However, if the generator rotor has enough mass, it may have enough inertia to keep the engine running fine with an aluminum flywheel. Just experiment.

Go with solid state ignition if possible. Ignition points were fine in their day, but the solid state magneto's are great!

Make sure the speed governer works and that the engine is cleaned and serviced reguarly.

The small gas tank on these B&S will give you at least an hour of power. If you need longer running time, then find an engine with a larger gas tank. A gallon tank will give you lots of time with a small engine, probably over 4 hours or so before refueling. Check oil levels at each gas refill, etc.

If you experience static on radios or TV's that you are powering by your generator: Sometimes ignition static can be a problem. Rubber boots should be placed over the sparkplug wire so that there is no wiring uninsulated, and then simply cover the sparkplug wire with braided wire and ground it near the magneto coil. Also clamp it around the sparkplug metal base. That will cure it.

Static can be caused by the generator rotor bearings. (I have yet to have that problem!) But, just in case you do: Simply mount a little contact brush against the shaft of the generator rotor and that will successfully ground it and eliminate the static.

Once again I've got to thank Dewey King, NJ8V, for his never ending patience and help with the mechanical hurdles! His expertise in machining leaves me bewildered.

Misc.

A. This motor exhibits an internal resistance of about 1.5 ohms of AC resistance and .5 ohms of DC resistance.

B. The capacitor current is approximately 11 amps. Remember, this current exists whether there is a load or not. However it is not 100% "real power", but it is capacitive, with the current out of phase with the voltage. The current, I, leads the voltage, E, in this case. The reason this current exists is to keep the generator "excited" by inducing current into the squirrel cage rotor conductors. Calculations seem to put the exciting power at around 55 watts.

C. The reactance (Xc) of the capacitor (200 uf) at 60 hertz is 13.3 ohms.

D. The reactance (Xl) of the motor is (3.8 mh) at 60 hertz is 1.4 ohms

E. The capacitance and the inductance, being in parallel, does exhibit a resonance. This frequency is 183 hertz.

F. The engine needs to turn this generator at about 3700 rpm to give 60 hertz output. (If your motor is a 1725 RPM one, then you'll need it to turn at about 1875 RPM)

G. I don't have a clear understanding of exactly why this works... but it does!

Modified Dec 8, 1998